Warwick and Port Jervis 9/11 Plea Deal Angst

The plea deal cancellation by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin is now being evaluated by Col. Matthew N. McCall, military judge. Local family members of 9/11 victims discussed their perspectives.

Valerie Lucznikowska, who now lives in Warwick, was 60 and living in Manhattan when she learned that the World Trade Center Twin Towers had collapsed, likely burying her cherished nephew, Adam Arias, who was 37. She was nearing knee replacement surgery, and standing was painful. But she stood in line for four and a half hours at the coroner’s office to register her nephew as missing. Later she went from hospital to hospital to see if he had been found.

“My adrenaline was so strong, I didn’t feel pain,” she said. “Victim centers didn't form immediately. I think it was the next day the first one opened. At first, they had lists of those killed and bodies found. After another day or so, the lists were only of body parts found. My nephew's name was not on any of them. My family wasn't notified until the next week that his body was recovered. Weeks later I learned from the coroner that his was the eighth body found.”

As sorrow, frustration and anger among survivors grew, Lucznikowska said, “I was looking for a just outcome. Justice holds society together. I wanted a trial in New York under federal law. But many want the death penalty and don’t understand that the trajectory won’t lead to that. The formation of the military commissions to try those accused of ‘war on terror’ crimes has no history to set precedent. The law being used applies either federal or military law, as determined along the way. The finding of torture can mitigate a death sentence. This has been a factor pointing to plea deals as a way to short circuit the proceedings.

“The plea deals recently signed by three of the accused require life sentences without parole. The deals also require them to answer questions from those harmed by their actions. They would have to explain how and why they did what they did. This would not be required by a court finding of guilty. “

Lucznikowska wants peace and justice, not vengeance and violence, which, she says, leads to more of the same. She pointed out that, in the 23 years since the attack, Adam’s mother has died, as have several other of his close relatives and many relatives of other victims.

“Is that justice if everyone dies and leaves the whole thing up in the air?” Luczinikowska, who is now 85, asked.

However, the plea agreement recently reached for three 9/11 defendants was rescinded two days later by Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin. Whether Austin has the right to cancel the agreement is now being considered by the judge in the case, Col. Matthew N. McCall. While many 9/11 survivors may oppose it, Lucznikowska is not alone in supporting it.

What impedes justice, she said, is the way 9/11 suspects were treated once detained. She noted the use of what have been called “black sites” in Afghanistan, Lithuania, Morocco, Poland, Romania, and Thailand, as well as Guantanamo Bay, to house prisoners and torture them to get confessions.

“In 2002, the first prisoners were held in open air cages in Guantanamo Bay. The federal district court couldn’t exercise habeas corpus over them. They were denied Constitutional rights,” said Lucznikowska.

Meanwhile, in the spring of 2002, she went to a demonstration at the office of Senator Chuck Schumer carrying a poster of her nephew’s photo above the words, “Not in his name,” opposing war in Iraq as revenge for the 9/11 attacks.

Also at the demonstration was Rita Lasar, who handed Lucznikowska a pamphlet about a group, September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, a name derived from Martin Luther King’s statement, “Wars are poor chisels for carving out peaceful tomorrows.” Lasar’s brother had been assisting a parapalegic man on the 26th floor of the World Trade Center when he was killed, Lucznikowska said. She joined the group, and for the last 22 years has communed with them via email and occasional gatherings, as they advocated for plea agreements. They aimed for some kind of justice in which the suspects would never be released and would acknowledge what they had done. Lasar died seven years ago.

The suspects were ultimately arraigned in 2012 in a military commission court, Lucznikowska said. Pre-trial hearings, deciding what evidence would be permissible, have preoccupied the past 13 years for the defendants’ cases because of the conditions of their captivity, which included repeated torture.

Only three of the five accused at Guantanamo Bay were involved in the plea agreement. The plea agreement Lucznikowska and her cohorts supported would include a sentence of 2977 days, a day for each 9/11 death as well as the requirement that the men answer questions from survivors.

“We pushed the convening authority, Harvey Rishikof, on it. He was fired. They kept naming new convening authorities. Susan Escallier had only been in the position for a year,” when a plea agreement was reached, Lucznikowska said. “Austin’s invalidation of the plea deal came as a wild shock, like lightning striking. It came out of nowhere. It’s illegal. He’s overridden the convening authority.”

Lucznikowska noted a summary of responses to the plea agreement detailed in a publication by the Lieber Institute at West Point:

“Reaction from the families, the public, and Congress was swift, negative, and public. Concerns included fears of foreclosure of access to the co-conspirators, as families continued to press their case in federal court to hold Saudi Arabia accountable for its complicity in the 9/11 attacks; removal of the death penalty as punishment for the murder of their loved ones; and the potential for the defendants, once incarcerated for life, to go free in a prisoner-swap much like the one struck by Washington and Moscow that very week.”

“No one knows why Secretary Austin negated the plea deal's initial signed agreement,” Lucznikowska said, but added, “I had an uncorroborated guess. Concurrent to the military commission’s ongoing 9/11 and Cole cases, a group of 9/11 family members has brought a case under federal law against Saudi Arabia for 9/11 facilitation. It’s not the legal charge, and my group is not party to this. My guess is that Austin's action is on behalf of the U.S. government which has pushed back against the idea of accusing Saudi Arabia. The new Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA) is a law that allows lawsuits against foreign states for certain terrorism-related conduct.”

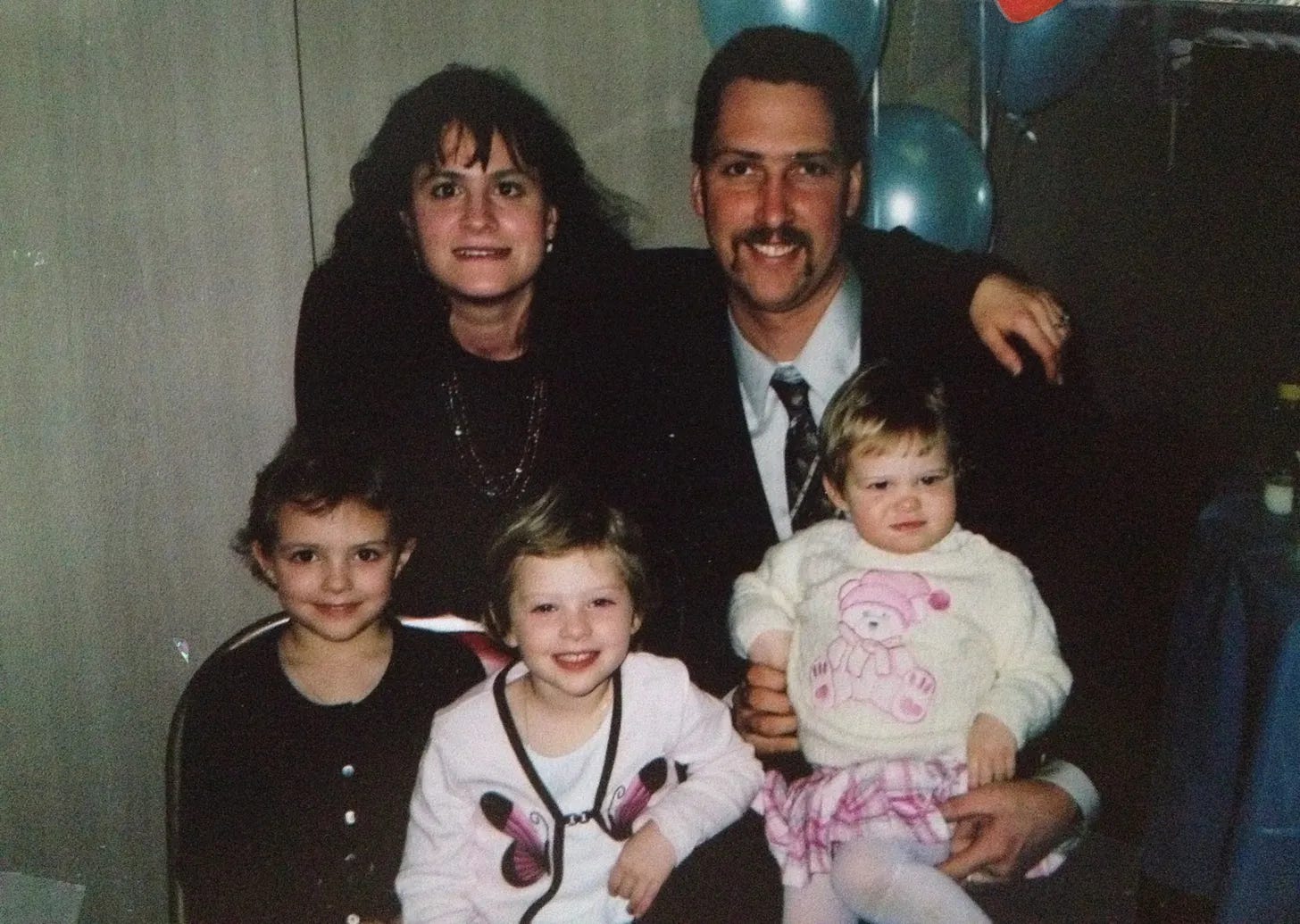

Also upset by Austin’s cancellation of the plea agreement was Elizabeth Miller, of Port Jervis, who befriended Lucznikowska as, four years ago, she too began participating with September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows. She was six when, perched on her bed in Port Jervis, her mother told her and her two sisters that their firefighter father would not return. He had been lost in the Twin Towers conflagration.

She is now project director for September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows and, like Lucznikowska, has visited Guantanamo Bay several times, sitting in a glassed in area to witness and hear, on a delayed recording, the interminable pre-trial hearings. She was relieved when she received a call about the plea deal approval by the convening authority for three defendants, along with information about how to submit questions to them.

“I was shocked,” she said of then hearing that the plea agreement had been cancelled. “The military commission system is failing 9/11 family members.”

For her, the plea deal was a breakthrough after the 13 years of pre-trial hearings, focused on what testimony was admissible, after torturing defendants made the validity of their statements questionable.

“Thirteen years is a very long time,” said Miller. “If the men captured were not tortured and had been brought to the U.S. to stand trial, it would be over. But they were allowed to be tortured at black site prisons,” making the validity of their subsequent statements questionable, possibly given to stop the torture.

She pointed out that while Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, considered to have plotted the 9/11 attack, is a “terrible man,” he was waterboarded 183 times, “walled” repeatedly—his head banged against a wall, and kept naked and diapered. He, with two accomplices, Walid bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi, signed the plea agreement. A fourth defendant, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, was found mentally unfit to stand trial; his lawyer attributed his delusions to torture.

The prosecution had agreed to consider a plea deal in March of 2022, Miller said. In August of 2023, President Joe Biden had then rejected plea deal principles that included health care and prison location provisions. A new plea deal was then worked out with newly appointed convening authority Susan Escallier, who had been appointed by Austin. The agreement was accepted by the prosecutor and defense team.

“Austin had authority to stop the plea deal, but the question is why. My personal belief is that he was convinced by others that it was a bad idea. But anyone who went to Guantanamo Bay could see that a plea agreement was the only way. It was an opportunity to ask questions. A trial wouldn’t allow survivors to ask questions,” said Miller. “The result is an abundance of litigation, mess and delay. All are in limbo, waiting to see what’s next. How can you have a jury trial when the men already said they were guilty? A trial with a death penalty verdict would have led to years of appeals, while a plea agreement would guarantee no appeals.”

The plea agreement, which would have required the defendants to answer survivors’ questions about the 9/11 attack by the end of 2024, particularly appealed to Miller.

“I always wanted to know why they did it,” she said. “Information can be healing.”

She said she wants to know who else knew what they were doing and how close they were to Bin Laden.

“What was the trajectory? Who gave orders to send money?” she wanted to ask. “But two days after the plea deal approval, I heard on the news that it was cancelled. Austin should have said he would take time to evaluate the agreement. I don’t think he spent much time in Guantanamo Bay. He would have seen that a plea deal would be the only resolution.”

Miller had visited Guantanamo Bay three times and spent five of her 15 days there in court, she said. She learned the limits of what evidence can be used in court—not what is gained by torture or from classified information.

“Now they’re still arguing. Why not trust who he appointed? He acted like the deal was shocking news,” Miller said. “It had been discussed since 2022. The Nuremburg trials were quick, completed within a year. But 23 years after 9/11, it’s still not in the public record that Khalid Shaikh Mohammed is guilty.”

Miller acknowledges that many 9/11 survivors still want a death penalty trial and supposes that the plea deal cancellation resulted from pressure by families, the public and government officials. But not only does she not expect that such a trial would result in a death penalty, she does not support it.

“I’m not God. No human should decide who lives,” she said. “Spending life in prison is enough. The information they can provide is worth more than them being dead. Mohammed came up with the idea that killed our loved ones. The plea deal gave us a way to ask why.”

Community focused news can only succeed with community support. Please consider the various subscription levels.