Centuries Old Milford Serial Murders Reconsidered in Film Fest Documentary

"Burying the Hatchet," a documentary produced by Milford Mayor Sean Strub, will be the opening night film at the Black Bear Film Festival on Oct. 18.

When Sean Strub became mayor of Milford Borough in 2016, in addition to his routine mayoral duties, he wanted to address a violent chapter in the town’s history, when it erected a monument in honor of a serial killer in the 19th century.

He became Milford mayor after years of activism to clear the cloud around AIDS and HIV, including launching the magazine POZ in the 1990’s.

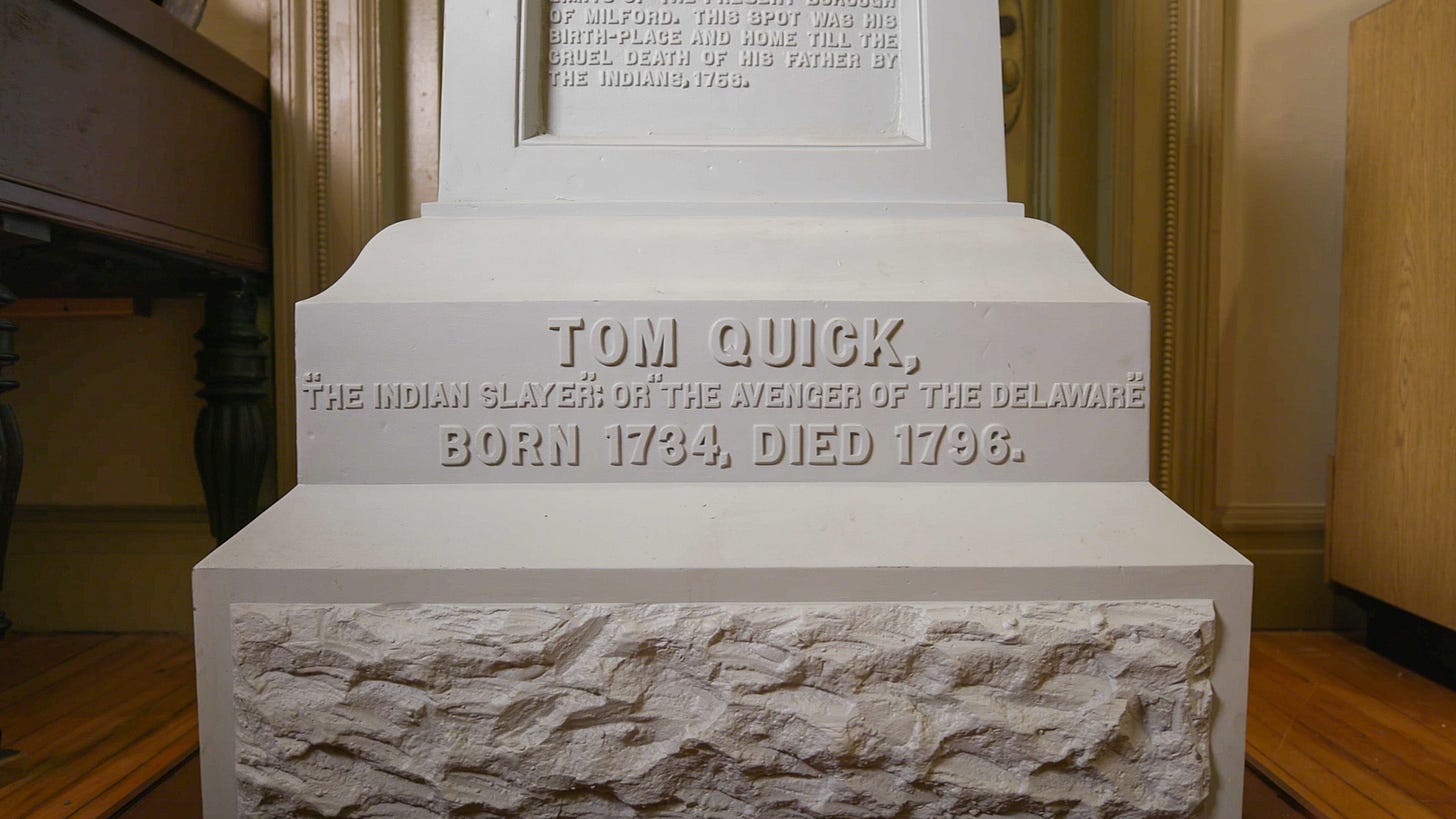

He saw the embodiment of Milford’s misunderstood history in a monument dedicated to Tom Quick, Jr. It had stood on Sarah Street, in a quiet, well-groomed neighborhood, although it celebrated a man who claimed to have murdered nearly 100 Native Americans. The victims were descendants of many generations who had lived on the land long before it became Milford in 1796.

“I knew the monument legend as told through the view of white colonialists,” Strub said.

But even when the monument was dedicated in 1889, he noted, newspapers in Port Jervis and Wilkes-Barre had questioned honoring the killer. The circumstances surrounding the murders and Strub’s efforts to rectify relationships with Native American tribes who had, for hundreds of years, inhabited the area are explained more fully in a documentary Strub produced, “Burying the Hatchet: The Tom Quick Story.” Written and directed by Christopher King, with Delaware Nation Hereditary Chief Daniel Strongwalker as associate producer, it will be shown on opening night at the Black Bear Film Festival, Oct. 18. In a recent interview, Strub elaborated on his path to the documentary and the local consequences of his efforts.

Asked about surprises he encountered, he recalled a library exploration that led him to the origin of the violent Milford saga. It stemmed from Benjamin Franklin’s only military commission, when appointed by the Pennsylvania colonial legislature. Tom Quick, Sr., in Milford, responded to Franklin’s call for a citizen militia to be led by Captain John Van Etten. Militia members were to be paid $40 per scalp of Indian combatants killed.

The aim was to drive the Indians off the land, although Quick previously had peaceful relations with local Indians. But they likely heard about the call for their scalps and Quick’s involvement, Strub said. Five days after Quick signed the document to join the militia, he was killed and scalped by Lenape Indians, to the horror of Quick’s son, Tom Quick, Jr., who, growing up, had played with Lenape children and learned their language.

His vengeance, killing nearly 100 Lenape Indians, was commemorated by the monument. When it was vandalized in the 1990’s, it was taken to Don Quick, a descendant of Tom Quick, to repair, and the Borough stored it in a garage for years.

Meanwhile, in the second half of the 18th century, the Lenape were driven away in an injurious “forced migration” to Texas and Oklahoma, where conditions were challenging and incompatible with their traditions. The white settlers and the Lenape tribes viewed and interpreted the Walking Purchase Treaty very differently, with the Lenape seeing it as an agreement about use of the land, not ownership, consistent with their culture’s different relationship with land, as noted in the documentary.

The film shows how Strub connected with leadership of the three federally-recognized Lenape tribes, long ago displaced from the Milford area, and also connected them with descendants of Cyril Pinchot. He had settled in what became Milford after fleeing France and Napoleon’s army after the Waterloo defeat, according to Peter Pinchot, Cyril’s descendant and heir to the land.

Although Cyril Pinchot had been involved with timber harvesting, his grandson, two-time Pennsylvania governor Gifford Pinchot, was a leader in the emerging conservation movement and served as the first head of the U.S. Forest Service, appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt. One result was extensive forest restoration and conservation around Milford. Gifford’s grandson Peter was heir to 1200 acres, a 10-acre piece of which would go to the tribes, toward “burying the hatchet.”

As for what was most challenging in this reconciliation effort, Strub said, “Each tribe is a sovereign nation, with their own system of governance, decision-making and differing priorities. It was like working with Italy, France and Germany, so learning how to respectfully work with each tribe was a challenge, but an interesting one. This is also a painful history, so it was important to remember that the Delaware Indians that Tom Quick, Jr. killed were all ancestors of the tribal members we were working with. It wasn't ‘just history’; it was about their families and their spirits.”

He recalled an unexpected moment during the gathering in the Fauchere conference room. He was sitting next to Chester Brooks, chief of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, one of the three sovereign Lenape tribes. Brooks put his right hand on Strub’s left hand and left it there, discomfitting Strub at first, he said. Then a warmth moved from Brooks hand to Strub’s hand and up his arm, into his chest. Brooks, who died in 2021, smiled.

“He knew what he’d done,” said Strub.

What did it mean? “Trust,” Strub said.

Community focused news can only succeed with community support. Please consider the various subscription levels.